When you think of “secret” agencies, you probably think of the CIA, the NSA, the KGB, or MI-5. But the real secret agencies are the ones you hardly ever hear of. One of those is the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). Formed in 1960, the agency was totally secret until the early 1970s.

If you have heard of the NRO, you probably know they manage spy satellites and other resources that get shared among intelligence agencies. But did you know they played a major, but secret, part in the Apollo 11 recovery? Don’t forget, it was 1969, and the general public didn’t know anything about the shadowy agency.

Secret Hawaii

Captain Hank Brandli was an Air Force meteorologist assigned to the NRO in Hawaii. His job was to support the Air Force’s “Star Catchers.” That was the Air Force group tasked with catching film buckets dropped from the super-secret Corona spy satellites. The satellites had to drop film only when there was good weather.

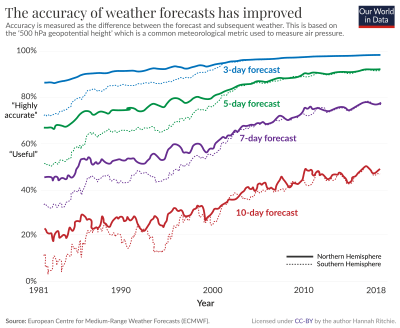

In the 1960s, civilian weather forecasting was not as good as it is now. But Brandli had access to data from the NRO’s Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP), then known simply as “417”. The high-tech data let him estimate the weather accurately over the drop zones for five days, much better than any contemporary civilian meteorologist could do.

When Apollo 11 headed home, Captain Brandli ran the numbers and found there would be a major tropical storm over the drop zone, located at 10.6° north by 172.5° west, about halfway between Howland Island and Johnston Atoll, on July 24th. The storm was likely to be a “screaming eagle” storm rising to 50,000 feet over the ocean.

In the movies, of course, spaceships are tough and can land in bad weather. In real life, the high winds could rip the parachutes from the capsule, and the impact would probably have killed the crew.

What to Do?

Brandli knew he had to let someone know, but he had a problem. The whole thing was highly classified. Corona and the DMSP were very dark programs. There were only two people cleared for both programs: Brandli and the Star Catchers’ commander. No one at NASA was cleared for either program.

Brandli knew he had to let someone know, but he had a problem. The whole thing was highly classified. Corona and the DMSP were very dark programs. There were only two people cleared for both programs: Brandli and the Star Catchers’ commander. No one at NASA was cleared for either program.

With the clock ticking, Brandli started looking for an acceptable way to raise the alarm. The Navy was in charge of NASA weather forecasting, so the first stop was DoD chief weather officer Captain Sam Houston, Jr. He was unaware of Corona, but he knew about DMSP.

Brandli was able to show Houston the photos and convince him that there was a real danger. Houston reached out to Rear Admiral Donald Davis, commanding the Apollo 11 recovery mission. He just couldn’t tell the Admiral where he got the data. In fact, he couldn’t even show him the photos, because he wasn’t cleared for DMSP.

Career Gamble

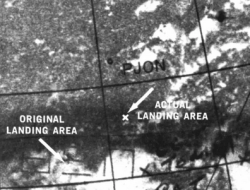

There was little time, so Davis asked permission to move the USS Hornet task force, but he couldn’t wait. He ordered the ships to a new position 215 nautical miles away from the original drop zone, now at 13.3° north by 169.2° west. President Richard Nixon was en route to greet the explorers, so if Davis were wrong, he’d be looking for a new job in August. He had to hope NASA could alter the reentry to match.

There was little time, so Davis asked permission to move the USS Hornet task force, but he couldn’t wait. He ordered the ships to a new position 215 nautical miles away from the original drop zone, now at 13.3° north by 169.2° west. President Richard Nixon was en route to greet the explorers, so if Davis were wrong, he’d be looking for a new job in August. He had to hope NASA could alter the reentry to match.

The forecast was correct. There were severe thunderstorms at the original site, but Apollo 11 splashed down in a calm sea about 1.7 miles from the target, as you can see below. Houston received a Navy Commendation medal, although he wasn’t allowed to say what it was for until 1995.

In hindsight, NASA has said they were also already aware of the weather situation due to the Application Technology Satellite 1, launched in 1966. Although the weather was described as “suitable for splashdown”, mission planners say they had planned to move the landing anyway.

Modern Times

Weather forecasting, too, has gotten better. Studies show that even in 1980, a seven-day forecast might be, at best, 45 or 50% accurate. Today, they are nearly 80%. Some of that is better imaging. Some of it is better models and methods, too, of course.

However, thanks to one — or maybe a few — meteorologists, the Apollo 11 crew returned safely to Earth to enjoy their ticker-tape parades. After, of course, their quarantine.

Heck, even the NSA has a museum ( https://www.nsa.gov/museum/ ), which is worth a visit if you’re in the DC area. NSA’s website is pretty interesting, and they have a lot of history pages. CIA has a museum, too, but you can’t see it unless you work there (so you know it’s good)…

GCHQ (The UK equivalent of the NSA) have a museum too, but alas it’s not open to the public. Given that they’re the inheritors of Bletchley Park, they probably have some of the very earliest computers in there.

Bletchley Park itself and the co-located TNMOC are well worth it, the Science Museum in London also had some stuff from GCHQ for a while although that may have been temporary.

It seems quite possible that NASA claimed to have already made the decision to move the landing site as cover for the classified information. A lot of disinformation goes into protecting classified info.

Wait, how do ppl on the ground change the landing zone ?!

Most of the navigation was done from the ground. Change what the flight controllers tell the crew, and you change where the capsule lands.

I’ll be honest and admit that I don’t know how much of it was manual (flight control tells the crew what to do, who then does it) or how much was automated (flight controll sends commands electronically to the computer on the lander.)

I knew what to ask Grok 3:

The Apollo Command Module’s computer, known as the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC), played a critical role in improving the accuracy of splashdown during reentry and landing by performing precise calculations, integrating real-time data, and enabling course corrections. Here’s a concise explanation of how it achieved this:

Navigation and Trajectory Calculations: The AGC used inertial navigation, relying on gyroscopes and accelerometers to track the spacecraft’s position, velocity, and orientation relative to Earth. It continuously calculated the spacecraft’s trajectory based on this data, predicting the reentry path and splashdown point with high precision.

Reentry Guidance: During reentry, the AGC ran a sophisticated guidance program called the Entry Monitoring System (EMS). This program used a precomputed reentry corridor (a narrow range of acceptable flight paths) and adjusted the spacecraft’s attitude to control lift and drag. By modulating the Command Module’s roll angle, the AGC could steer the spacecraft to stay within the corridor, correcting for deviations caused by atmospheric variations or navigation errors.

Real-Time Data Integration: The AGC processed inputs from onboard sensors and ground-based tracking data (when available) to update its calculations. It accounted for variables like atmospheric density, spacecraft mass, and velocity, refining the predicted splashdown point as the reentry progressed.

Closed-Loop Control: The AGC operated in a closed-loop system, meaning it continuously compared the actual trajectory to the desired one. If deviations were detected, it issued commands to adjust the spacecraft’s orientation, ensuring the trajectory aligned with the target splashdown zone.

Precomputed Landing Zones: Mission planners provided the AGC with target coordinates for splashdown, based on recovery ship positions and safety considerations. The computer used these as a reference to guide the spacecraft to a precise location, typically within a few miles of the intended point.

Backup and Redundancy: The AGC had backup programs and manual override options, but its primary mode was automated guidance, which reduced human error and improved accuracy compared to fully manual systems.

By combining these capabilities, the AGC enabled Apollo missions to achieve splashdown accuracies within 1–2 nautical miles of the target, a significant improvement over earlier space programs. For example, Apollo 11 landed just 2.4 miles from the recovery ship USS Hornet, demonstrating the system’s precision.

The Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) and associated systems were amazing for their time and, for that matter, amazing even for our time:

Apollo Guidance Computer Part 1: Restoring the computer that put man on the Moon

CuriousMarc

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2KSahAoOLdU

From Wikipedia:

A different sequence of computer programs was used, one never before attempted. In a conventional entry, trajectory event P64 was followed by P67. For a skip-out re-entry, P65 and P66 were employed to handle the exit and entry parts of the skip. In this case, because they were extending the re-entry but not actually skipping out, P66 was not invoked and instead, P65 led directly to P67. The crew were also warned they would not be in a full-lift (heads-down) attitude when they entered P67. The first program’s acceleration subjected the astronauts to 6.5 standard gravities (64 m/s2); the second, to 6.0 standard gravities (59 m/s2).

What’s amazing is the accuracy of all of the Apollo landings. They could have safely landed off the coast of Florida just like, until recently, Musk’s Dragons. For example, Apollo 11 landed about 2.5 miles from its target, and Apollo 13, despite its challenges, was within 1 mile.

Another not well known space fact: The Soviet’s Luna 3 which was the first to photograph the far side of the moon used the very special film type from a captured US spy balloon of Project Genetrix:

“Project Genetrix, also known as WS-119L, was a program run by the U.S. Air Force, Navy, and the Central Intelligence Agency during the 1950s under the guise of meteorological research. It launched hundreds of surveillance balloons that flew over China, Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union to collect intelligence on their nuclear capabilities. The Genetrix balloons were manufactured by the aeronautical division of General Mills. They were about 20 stories tall, carried cameras and other electronic equipment, and reached altitudes ranging from 30,000 to over 60,000 feet, well above the reach of any contemporary fighter plane. The overflights drew protests from target countries, while the United States defended its action.”

Faxes From the Far Side: The 1950s-era Soviet mission to first photograph the far side of the moon.

https://www.damninteresting.com/faxes-from-the-far-side/

I’d be curious to see an updated chart of that “forecast accuracy over time” chart, it only goes up to 2018. It feels in the last year or so those predictions have gotten worse.

DMSP passive microwave data reprocessed and cleared for civilian use is available at the NSIDC NASA DAAC.